All mountains have their secrets.

The Santa Ynez range rises 4,000 feet above Santa Barbara. For a mountain range, Santa Ynez is a youngster at only 5 million years. She is stretching up from a bend in the San Andreas fault and unlike most mountain ranges runs from east to west. She first spoke to me when I was 10 years old. We met through the picture window in my godparents’ home in Carpinteria. At first I thought she was a painting.

Her first children were the Chumash, living off of the plentiful game, fish, and sea life. There were floods, fires, and earthquakes, but mother and children lived in harmony for 13,000 years. Then Gaspar de Portola came with soldiers, and settlers. The missions and the ranchos came. The diseases came. The Americans came. Now, but a handful of the Chumash are left.

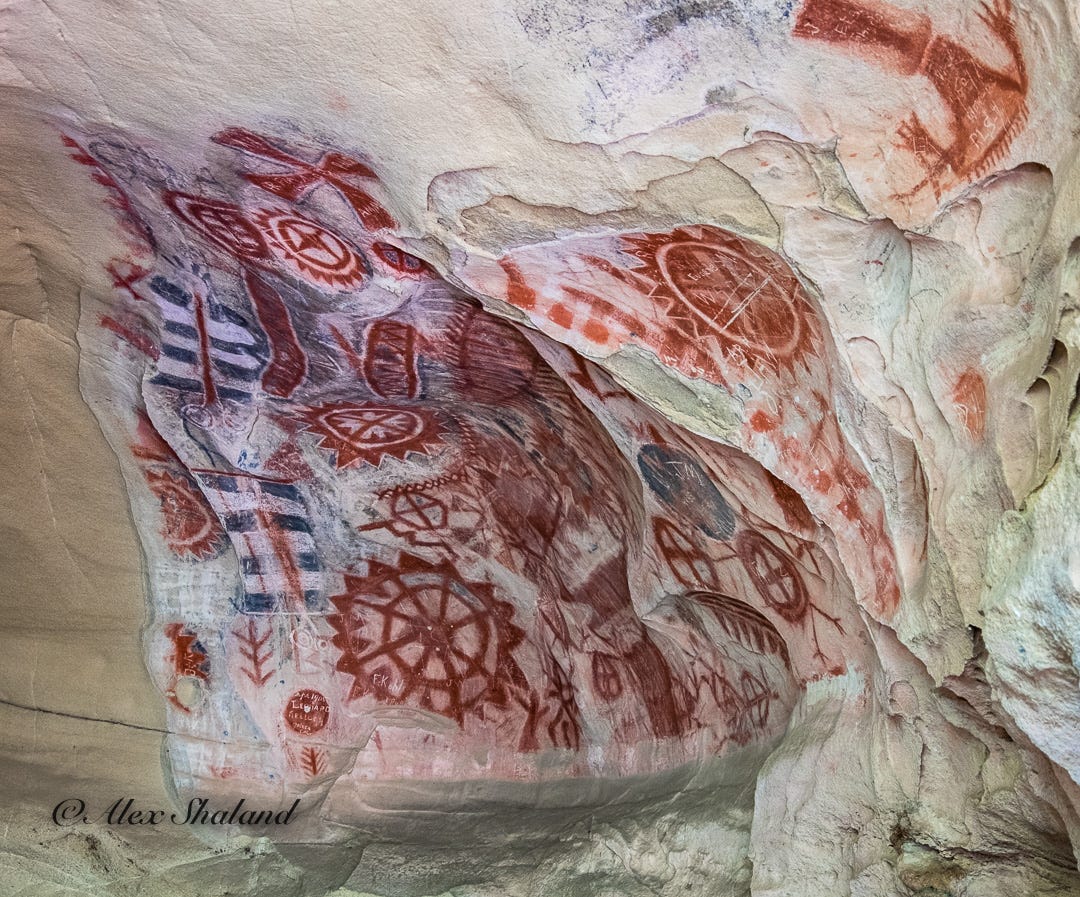

The Painted Cave State Park reveals another of the mountain’s secrets as recorded by the Chumash. A total eclipse of the sun with Mars and Antares may be recorded in the Painted Cave State Park.

In the late 1800s, wealthy Americans built their winter homes and many came for the healthy climate and the beauty. Farms and orchards overtook the mission lands, the slopes, and the creek beds.

Many make the mistake that the mountain is a backdrop, but the beach and the immigrant palms are actually a wrinkle on her apron.

We got better acquainted when I helped my godfather, who was the groundskeeper at an estate in an exclusive enclave higher up on the mountain - Montecito. Nearby was an old ranch called Queen of Peace.

In 1968, the country was convulsed by the war in Vietnam, with the rising counter-culture of hippies and folk singers giving way to sex, drugs, and rock and roll. We were on our way to the Moon even as we endured the killings of Robert F. Kennedy, Jr, and Martin Luther King, Jr. Pope John XXIII had died after succeeding in his quest to “let some air in.” The Catholic Church was undergoing a transformation not seen since the Reformation.

That’s the year I entered the Jesuit Novitiate in Montecito, The College of the Queen of Peace. It was brand new and built to complement the mountain with its brick and tile facade that reflected the mountain and protected the buildings from the sun, salt, and wind.

It was a place of reflection, study, work, and the raucous disturbances of young men. We were finding our way in a world of Ignatian spirituality from the 1500s that focused on finding God in All Things at a time when God had been declared dead. The mood was a conflicted progressiveness, as older members of the order suffered the same generational shock that afflicted everyone else. We carried our draft cards and went to work in hospitals, in the inner city, and in schools.

The College of the Queen of Peace is now the Pacifica Institute and the Jesuit Novitiate is now in the hustle and bustle of Culver City - a place more in keeping with solidarity with those left behind in Los Angeles.

When I return to Montecito, I find a solace in Our Lady of Mount Carmel. It is a place that evokes what is deep inside me and still growing after my first sojourn on the mountain. In a city built in the Mediterranean or Spanish styles, Our Lady of Mount Carmel is out of place. It is a portal to the Jesuit churches of New Mexico, but built in 1938. It was funded by three wealthy women who had moved to the area.

The natural lighting in the church creates unusual effects that take me to other places. It creates an unusual dimensionality that shifts its intensity and bounds with the sun. The mountain still speaks to me, but even now, she keeps her secrets.